Nazimuddin Mondal (34) recalls that he was slapped before being asked to sing the national anthem. “At the police station they told me to sing it and then checked my phone to see if there were any phone numbers from Bangladesh,” he says.

Mr. Mondal says life had been going smoothly for about a year and a half in Mumbai’s Nalasopara area, where he lived on rent. With a daily wage of ₹1,300, the migrant from Tartipur village in Murshidabad district, West Bengal, had come to Maharashtra to work. On June 9, 2025, there was a knock on his door. Men in uniform had come for him. They took him to the local police station. Mr. Mondal recalls that there were 13 Bengali-speaking men at the police station. Then began a journey of about 2,500 kilometres spanning six days.

From the police station in Mumbai, Mr. Mondal says he and a few others were taken for a medical check-up, then driven to Pune the next morning. He recalls that they were put on a flight from Pune to West Bengal, their hands in zip-ties.

After landing somewhere in north Bengal, Mr. Mondal says he was driven along the international border in the early hours of one morning and pushed into Bangladesh.

“The men in plainclothes forced me to cross the border. It was the scariest day of my life,” he says. He was handed ₹300 in Bangladeshi currency, a packet of food, and a bottle of water. “‘You all are Bangladeshis,’ the man told me in Bengali, threatening to shoot me if I tried to return.”

Three migrant workers from West Bengal picked up from Maharashtra and allegedly pushed into Bangladesh in June 2025.

On June 14, 2025, a video of him and two others, Minarul Sheikh and Mostafa Kamal Sheikh, both also migrant workers from West Bengal, allegedly picked up by the police in Maharashtra, surfaced on social media. Sitting in an open field, the men cried out to the West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee for help: “Mamata (Banerjee) Didi please save us… We have been pushed into Bangladesh.” The next day, the three were repatriated through the India-Bangladesh border close to Mekhliganj town of Cooch Behar district, West Bengal.

Across India, thousands of Bengali-speaking migrants are being asked for documentation to prove their Indian citizenship. The crackdown began, say sources in the Home Ministry, after the regime change in Bangladesh in August 2024. The questioning intensified after the Pahalgam attack on April 22, 2025. Ms. Banerjee alleges that the intensity of it is felt most in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-ruled States.

The Delhi Police has checked documents of over 16,000 Bengali-speakers over the past few months. The Haryana government had set up detention centres in July where they allegedly held people. In Gujarat, over 1,000 were detained in Ahmedabad and Surat. Through June and July, migrant workers have been leaving jobs in other States to return to West Bengal.

Almost a month after the incident, Mr. Mondal is back home. He wears the same shirt in which he was seen in the video, and is struggling to find work in his village. “The contractor (in Mumbai) is calling me regularly, but I have no documents; they were all taken by the police. Here, even if I get work, I don’t get even ₹500 a day,” the migrant worker says.

The village, located along one of the distributaries of the Ganga, has a standing crop of jute in July, rising to almost five feet. The roads are filled with potholes so deep that ducks swim in them. Most men in the village migrate out of West Bengal for work, though there is no reliable data on how many do.

Going back to work

Less than a kilometre from his house, is a locality where other migrant workers have been forced to return from their place of work. They were detained for three days in the neighbouring state of Odisha. They were part of a group of about 400 who were detained by the Jharsuguda police in Odisha during the second week of July.

On July 9, 2025, the Trinamool Congress (TMC), the ruling party in West Bengal, posted a 55-second video of the workers on social media. In the video, Samiul Ansari (31) is describing how they were picked up in the dead of night.

At their village in Murshidabad, Mr. Samiul Ansari is joined by four others: Yeasmin Ali Ansari (50), Manaruzzaman Ansari (41), Newton Ansari (33), and Amanat Ansari (31). They sit in a circle and narrate their ordeal during detention for 72 hours. By Indian law, police can detain a person for no longer than 24 hours, before which they must be produced before a magistrate.

“The police did not beat us at the detention centre, but kept saying that they had orders from above to detain us,” Mr. Samiul Ansari says. The men, who were detained in Jagatsinghpur district in Odisha, say they have been going to the State for a decade to work; this was the first time they had faced trouble. Odisha’s government is run by the BJP that came to power last year.

“There is no work here. Maybe we won’t go to where the police had detained us,” they say. The three younger men in the group went back to Odisha 11 days later.

Their greatest fear is what identity documents they should carry so that the police does not detain them. In the village, Razzak Sheikh, the father of two migrant workers, has filed a habeas corpus petition before the Calcutta High Court, when his sons were detained elsewhere in Odisha. “I got a call from the police there, who threatened to push my sons into Bangladesh if we failed to produce birth certificates.”

In Murshidabad, Razzak Sheikh, the father of two migrant workers, has filed a habeas corpus petition at the Calcutta High Court.

| Photo Credit:

Shiv Sahay Singh

Having an Indian birth certificate is, however, no guarantee say migrant workers, that they will not be harassed. Amir Sheikh, 19, from Malda’s Kaliachak area, who was allegedly jailed in Rajasthan for a week before being pushed into Bangladesh in May 2025, had one, say his parents.

Up to 1,000 people were identified as suspected Bangladeshi nationals, detained, and sent to six detention centres, in the State. The parents have produced their passports too, but say their son is still stuck in Bangladesh. On August 7, 2025, the father filed a habeas corpus before the Calcutta High Court.

Amir Sheikh 20, year old migrant worker was allegedly picked up from Rajasthan in May 2025 and pushed into Bangladesh by security agencies.

On July 30, 2025, the Maharashtra government claimed that 42,000 ‘fake’ birth certificates issued to ‘Bangladeshis’ had been cancelled, and the number to be further cancelled by August 15 would be far higher.

Politics at play

In the first week of May 2025, weeks before these stories of migrants alleging detention and pushing into Bangladesh surfaced, TMC Rajya Sabha MP Samirul Islam wrote a letter to Mr. Shah. In it he claimed there was a “disturbing pattern of targeted hostility” against Bengali workers in BJP-ruled States such as Gujarat. Mr. Islam is the chairperson of West Bengal Migrant Welfare Board.

By the second week of July, reports of migrant workers in different parts of India began surfacing almost daily in West Bengal. On July 16, 2025, Ms. Banerjee hit the streets in Kolkata and warned that protests would rage across the country if Bengali migrants continue to be harassed.

Two days later, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, while speaking at a public meeting in Durgapur in the southern part of West Bengal and one of India’s main steel-producing centres, said that “Bengali asmita” (identity and culture) was paramount to the BJP, but emphasised that “whoever has infiltrated into the country will be dealt with as per law”.

Kolkata’s youth, on Bengali ashmita

“As a non-binary person, I find the most freedom in expressing myself through Bangla. It doesn’t confine me to gendered pronouns: I can simply be a ‘tui’ or ‘tumi’ to those I love. My Bengali identity thrives in Satyajit Ray’s films, in the comfort of aloo-sheddho bhaat, and in the Durga Pujo essays I wrote every year in school, guided by my grandfather’s handwritten notes.” —

Zoya Khan, filmmaker, 27

“Political movements, intelligence, culture: Bengalis have always been at the forefront of these things.” —

Pratyasha Pal, a post-graduate student of History, 23

“Bengali identity is the Bengali language, Durga Pujas, and football. The way we express ourselves in Bengali, our mother tongue, is crucial to expressing our true emotions.” —

Guddu Adhikari, hospital intern, 21

“We have a lot to be proud of, as Bengalis, like our literature and our freedom fighters.” —

Soumit Choudhury, journalism student, 19

“To me, anyone who speaks Bangla is Bengali. There isn’t a divide if you are Hindu or Muslim or where your place of origin is. As a student of Bengali literature, I am very attached to our great writers: Rabindranath Tagore, Jibanananda Das, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay.” —

Riya Nayak, Bengali literature student, 19

“Bangla is our mother tongue, and to me, that is the most important aspect of being Bengali.” —

Aniket Pal, voice actor and blood bank staff member, 25

“Bengali identity is everyone who speaks in Bengali, be it in West Bengal, Tripura, or Bangladesh. It is our mother tongue, and that is where our identity lies; it is a shared identity.” — Abhinab Das, student of philosophy, 20

“If there is anything called Bengali ashmita, then it is a reaction to what is happening in our country right now. Before, this identity was more cultural; now it is a matter of ego as well.” — Rushati Saha, illustrator and graphic designer, 25

“For me, my Bengali identity is associated with Durga Pujas, football, and staying in Kolkata. I was raised in Lucknow, so my exploration of the conventional Bengali culture has been limited.” —

Pritam Sarkar, studying Comparative Literature, 20

“Bengal’s culture and heritage are great, but the current rate of unemployment and lack of opportunities in West Bengal make me wonder if I have enough to be proud of.” —

Shinjini Guha, MBA student, 21

“My favourite part of being Bengali is being in love and expressing love in Bangla. This is the sweetest language in the world.” — Swarnali Adhikari, medical student, 24

“Even if our textbooks are in English and we learn in the English medium, the best way for me to grasp a concept is through Bengali. My mother tongue is behind my fundamental understanding of the world.”

— Saikat Duari, student of Mathematics, 20

1/3

On July 21, 2025, Ms. Banerjee addressed her party’s annual Martyrs’ Day rally. This is a commemoration of the day 13 people were killed in 1993, when police fired on the Youth Congress, then led by Ms. Banerjee. Before lakhs of supporters in Kolkata she claimed that the BJP government at the Centre “was unleashing terror on the Bengali language” and announced that a “language movement” would continue until the Assembly polls, due in 2026.

From the stage of the mega Trinamool event, the party chairperson read excerpts from what she called a secret notification issued by the Union Government in May 2025, and sent only to BJP-ruled States, which stated that if someone was suspected of being Bangladeshi, they should be detained for a month and sent to detention or holding camps.

Amidst thousands of migrants returning and the disruption of work, the debate on Bengali language and identity continues to rage. On August 3, 2025, the Delhi Police issued a letter referring to the Bengali language as Bangladeshi, which the Trinamool took up as an insult to the “Bengali-speaking people of India”.

The very next day, while justifying the action of Delhi Police, BJP IT cell chief Amit Malviya said, “There is, in fact, no language called Bengali.”

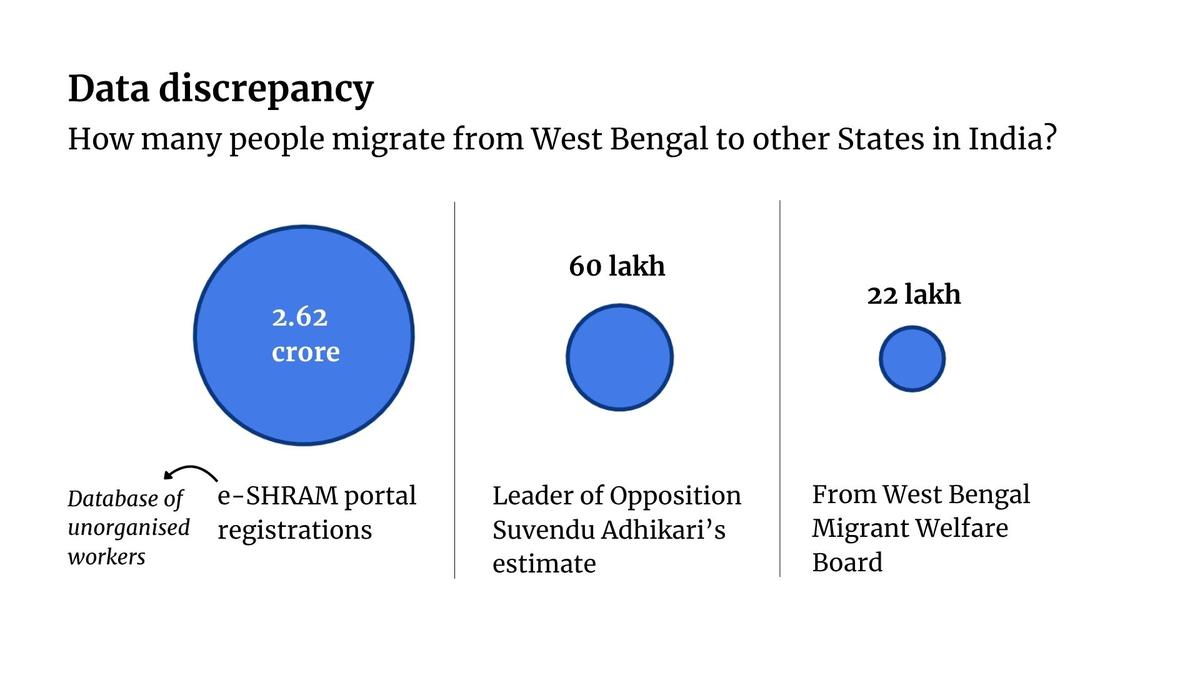

The West Bengal BJP leadership said that the drive is to identify Bangladeshi infiltrators and not migrants of the State. Leader of Opposition Suvendu Adhikari and newly appointed State BJP president Samik Bhattacharya speak of “sanitising the voter list and removing lakhs of Bangladeshi voters”. They insist on a Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of the voter list on the lines of what is happening in Bihar.

Economically speaking

The flight of industries and unemployment remain major challenges in West Bengal. The National Statistical Office’s (NSO) Annual Survey on Unincorporated Sector Enterprises (ASUSE) made public in 2024 pointed out that West Bengal lost 3 million jobs in unincorporated enterprises from 2015-16 to 2022-23.

In 2024, the Union Finance Minister had said that the share of industrial production in West Bengal had declined from 24% at the time of independence to 3.5% in 2021.

Economist Abhirup Sarkar, the chairperson of the West Bengal Infrastructure Development Finance Corporation, says, “There are historical reasons behind the decline of industries in West Bengal. One of the biggest factors is that Kolkata was dominated by British companies, which left after independence. Then, during the Left regime, militant trade unions and strikes played a role in the flight of capital.” He adds that productivity is low in West Bengal, but there is also a perception battle about the State.

More than a shared border

West Bengal shares a 2,216-km border with Bangladesh, and about 450 km of the border remains unfenced, making it porous in parts. Union Home Minister Amit Shah has said this is largely because the West Bengal government is not providing land to do so.

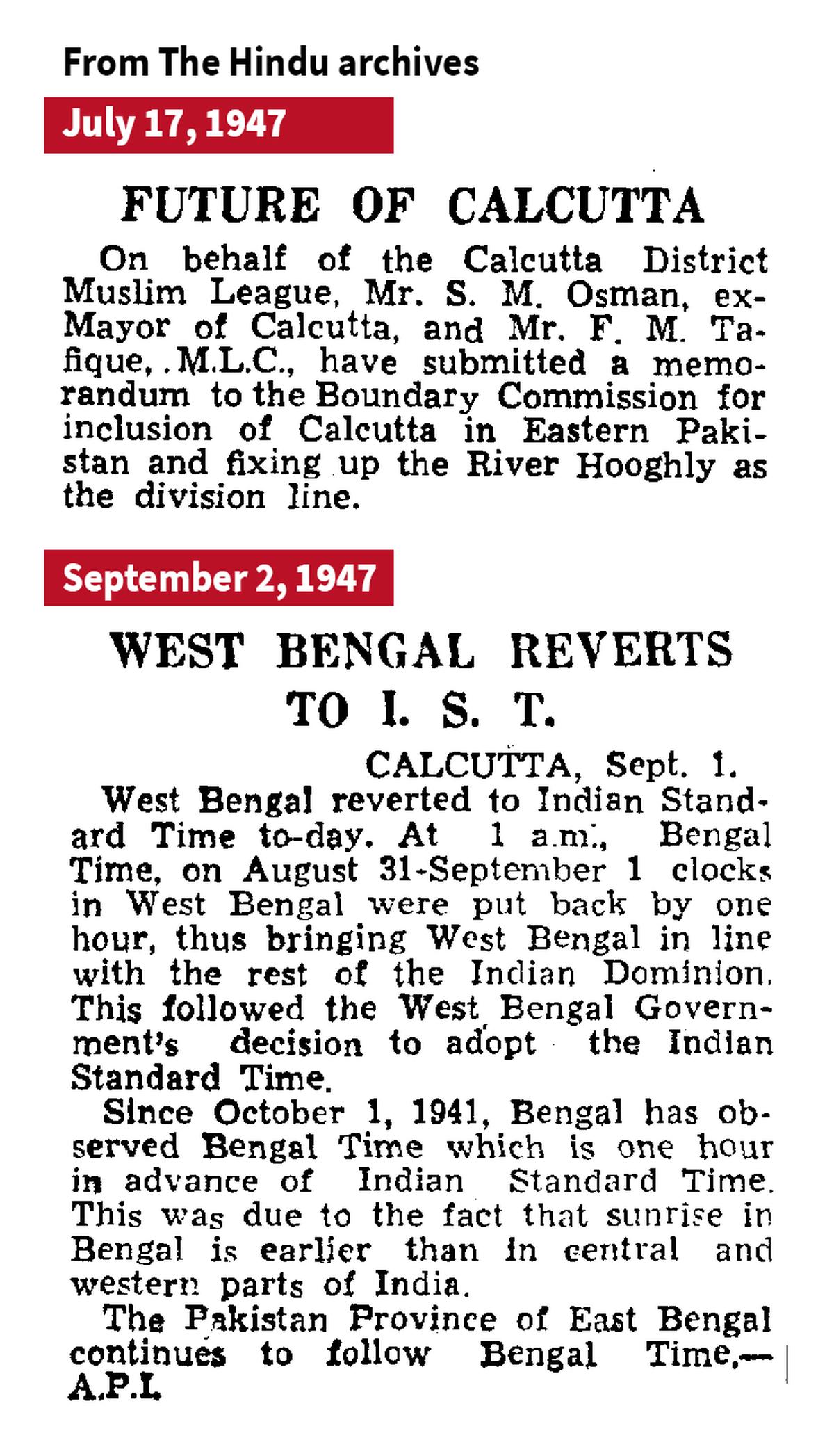

However, there are cultural, historical, and geographic ties between the Bengalis on both sides of the border. The partition of Bengal took place on Rakshabandhan day in 1905, when the then Viceroy of India, Lord Curzon, divided the Bengal Presidency into west (predominantly Hindu, including Bihar and Orissa) and east (predominantly Muslim, including Assam). This was annulled in 1911, when the capital was moved to Delhi.

However, there was further turmoil in 1947, when East Pakistan was formed, and people moved across the newly-formed border, on the basis of religion. In 1971, when Bangladesh was formed, another wave of people came to India.

Ten years ago, in 2015, a Land Border Agreement was signed between the two countries, where land parcels were exchanged, because there was Indian territory deep within Bangladesh and vice versa. People in these parcels were given the choice to become Bangladeshi nationals or Indian citizens.

Shamshul Haque and Rabiul Haque chose India, and migrated to Gurugram, in Haryana, to work. They were arrested on suspicion of being Bangladeshi nationals.

“We chose to come to India leaving our place of birth behind because we always thought of ourselves as Indians. I had never thought, even in my dreams, that I would be held on suspicion of being Bangladeshi,” Shamshul says, showing a citizenship certificate issued by West Bengal’s Cooch Behar district administration.

While the majority of migrant workers detained or pushed into Bangladesh are Muslims, there are some from the Matua community, a sect of Hindu Namashudras, Dalits who migrated from Bangladesh, who are also facing detention.

In Nadia district, two migrant workers from a Matua family, who had openly announced their allegiance to the BJP, were arrested by the Maharashtra police several months ago. Manishankar Biswas (23) and Nirmal Biswas (22) had left their home to work as carpenters in Akola district.Their father, Nishikanta, is an agricultural labourer. He and his wife, Pushpa, do not have the money to travel to Maharashtra. They live in a house put together with tin sheets.

Pushpa and Nishikanta Biswas, the parents of Manishankar Biswas and Nirmal Biswas, who were arrested by the Maharashtra police allegedly on suspicion of being Bangladeshi nationals.

| Photo Credit:

Shiv Sahay Singh

“We have had several cases of people of the Matua community being held by the police in Maharashtra. When the police pick up people on the basis of language, both Hindus and Muslims will be arrested,” says Nikhilesh Adhikari, a Nagpur-based lawyer who is trying to arrange bail for the two men.

On June 28, 2025, Ms. Banerjee urged migrant workers to return to West Bengal and assured them of work. Just a little over a month on, there are serpentine queues of migrant labourers at Howrah Station, booking tickets to leave again.

Rakesh Alam, 27, is boarding the Howrah Ahmedabad Superfast Express, leaving his four-month-old daughter behind. He says, “I cannot stay in Bengal when I have a family to feed.”

shivsahay.s@thehindu.co.in

Edited by Sunalini Mathew